GET OUT

It would be easy, and fairly accurate, to describe Jordan Peele’s Get Out as the horror-comedy flip side to Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner – kind of like what you’d get if the 1967 Sidney Poitier were less noble than monumentally panicked, and the Tracy-and-Hepburn clan were enacted by the Manson family. But that wouldn’t begin to suggest the singularity and incredible inventiveness of Peele’s achievement, which is so thrillingly scary-funny, and so deeply satisfying, that it might take you hours or days to also recognize it as one of the angriest genre entertainments ever made. Given the results, I couldn’t possibly mean that as a higher compliment.

In an ideal world, I wouldn’t even offer a review of Get Out until, say, next January, after the statute of limitations on spoilers had conceivably passed; while the movie is eminently worth discussing, what you really ache to talk about is how beautifully the odd details of the first half pay off in the second. What I can safely reveal is the setup, which finds the young, African-American photographer Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) invited by his white girlfriend Rose (Allison Williams, sensational) to spend the weekend at her parents’ remote estate. Chris is understandably apprehensive when Rose informs him that no, she hasn’t told them he’s black, and he’s hardly assuaged when she says not to worry, as her proudly liberal dad “would have voted for Obama a third time.” Still, off to her folks’ home they go, and after an unnerving highway incident involving an errant deer and a probing cop, Chris is greeted by Rose’s parents (Catherine Keener and Bradley Whitford, both perfect) with smiles, hugs, and “Welcome to the family!” bonhomie. This is what is known in horror films as a red flag. And the color palette only gets redder from there.

Jordan Peele, of course, is best known for partnering with Keegan-Michael Key in their iconic sketch-comedy series Key & Peele, a show that routinely said more about black identity in America during one three-minute skit than most similarly themed efforts manage over two full hours. And even while you’re enjoying Get Out’s early scenes and giggly/queasy fringe touches – such as Whitford’s explanation that their basement is sealed off because of “black mold” – you may still be somewhat dreading a potentially great Key & Peele short unfortunately elongated to feature-film length, much like last spring’s initially clever, eventually tiresome Keanu. Peele, however, is way ahead of us. As the behavior of the many whites and handful of blacks surrounding Chris grows from off-putting to sinister, Peele is masterful about systematically upping the emotional ante so that we feel our hero’s serio-comic disbelief, then increasing paranoia, then abject terror right along with him. (Kaluuya, so memorable as the romance- and revenge-minded cyclist in Black Mirror’s “Fifteen Million Merits” episode, is an empathetic, magnificently forceful presence here.) Peele is even better, though, at laying the groundwork for future shocks through seemingly casual, even throwaway bits of eccentricity – in terms of both action and character – that wind up having extraordinary cumulative impact.

How does the estate’s caretaker (Marcus Henderson), a slow-moving figure of dead-eyed smiles and languid vocal rhythms, have the energy to sprint toward Chris at top speed? Why does the family maid (a spellbinding Betty Gabriel) keep checking her hairdo in and on every reflective surface? How is one of the family’s other weekend guests – a blind art dealer played by the invaluable Stephen Root – so familiar with Chris’ photographic output? When Rose’s dad suggests a game of bingo, why is it played silently with already completed bingo cards? What does a tragedy from Chris’ childhood, and Mom’s gift for hypnosis, and the deceased grandpa’s obsession with Jesse Owens have to do with all of this? In his biting and magnificently structured screenplay, Peele keeps compounding the questions to the point that, like Chris, you feel nearly dizzy with confusion and dread. Unlike Chris’, however, it proves to be phenomenally enjoyable confusion and dread, given that when the answers come – and astoundingly, all the answers do come – they fit so logically into Get Out’s grand yet admittedly outré design that you’re left feeling simultaneously wiped out and exhilarated.

You’ll also, though, likely feel more than a little shaken, because while Peele is able to wring laughs out of everything from a hyper-suspicious TSA agent (the hilarious Lil Rel Howery) to a late-night wind-down of dry Froot Loops and the Dirty Dancing theme song, his themes are dead-serious. Clearly, Peele is aiming for uncomfortable laughs of recognition when Whitford uses dated “urban” slang to show off his liberal bona fides, or when a house guest, in discussing golf with Chris, can’t resist from offering a self-congratulatory “I met Tiger once.” But the laughs sting. Through the well-worn tenets of fright flicks, Peele is demonstrably connecting the dots between “well-meaning” Caucasian condescension toward blacks and uglier, more loathsome acts of racism, and when the ultimate “Why?” here is finally addressed, the explanation is legitimately horrific in its banality; Peele may frequently want us to chuckle, but he is also so not kidding. Fiendishly smart and unassailably thoughtful, Get Out may, in time, stand as a genre pinnacle, and it even saves a killer joke for the very end, as the last thing we see before the credits roll, in big block letters, are the words “GET OUT.” Obviously, we have no choice but to obey – even if we just get out long enough to grab some friends in time for another screening.

I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO

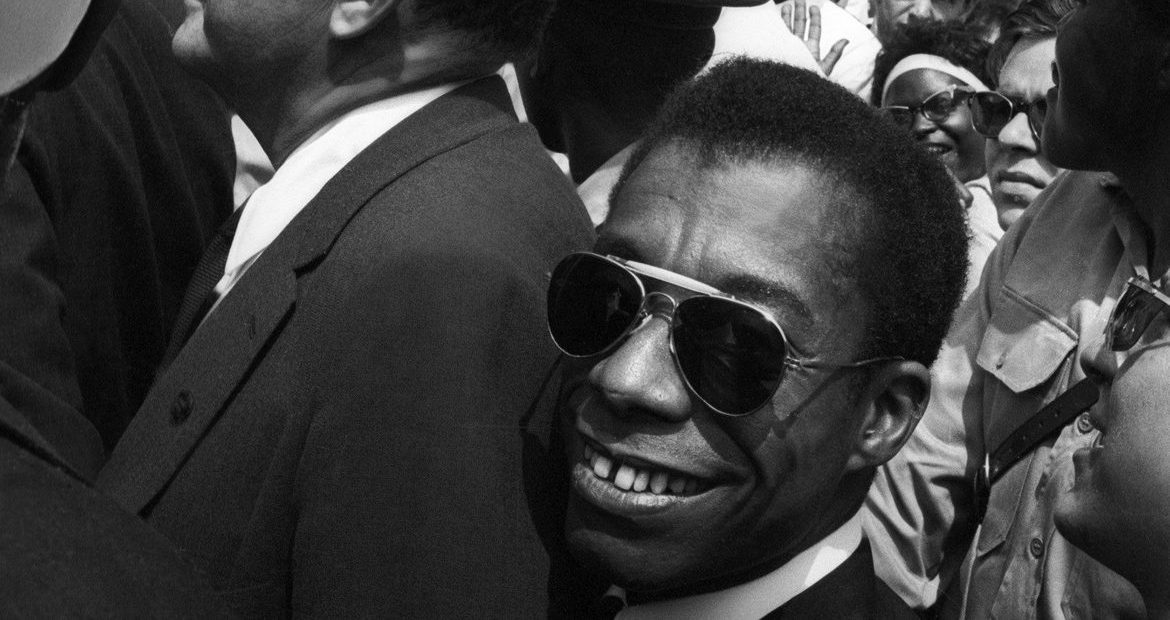

Although it would have made for a fitting (if eyebrow-raising) alternative title for Jordan Peele’s debut, I Am Not Your Negro is actually director Raoul Peck’s documentary on the black experience viewed through the life and times of esteemed essayist, lecturer, and playwright James Baldwin. If, like me, you’re ashamed of having been aware of Baldwin’s name and reputation without being remotely familiar with his work, Peck’s movie is unmissable – a stunningly detailed and moving primer on one of the most eloquent voices ever to speak on the subject of race in 20th Century America. (Hopefully, like me, you’ll also complement your movie-viewing by high-tailing it to your nearest bookstore to further educate yourself.) But in terms of both subject and presentation, I Am Not Your Negro is so sprawling, revealing, and extraordinarily insightful that to call it a Baldwin bio-doc is grossly insufficient; miraculously, Peck’s film manages to say as much about American race relations in 95 minutes as O.J.: Made in America does in more than five times that length.

With Samuel L. Jackson delivering perfectly calibrated readings from the author’s prose, much of it previously unpublished, it’s easy to be enraptured by Baldwin’s tumult of contradictory feelings: his optimism and despair; his frustration and patience; his frequent fear and occasional jubilation. Yet Peck’s entire movie maintains a sweeping sense of intellectual and emotional dynamism. There are photographs from the Jim Crow South to boil your blood and televised interviews from The Dick Cavett Show to drop your jaw. (In one such segment, Baldwin partakes in a panel discussion alongside Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, and Charlton Heston.) There are heartbreaking reflections on the deaths of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr., and snippets from “educational” industrial shorts that would make you cackle if you weren’t so appalled. (The most astonishing one is titled The Secrets of Selling the Negro.) There’s a mid-1960s Bobby Kennedy prophesying the emergence of a black president in 40 years, and trenchant exploration of Hollywood’s racial mindset in movies ranging from King Kong to The Defiant Ones to In the Heat of the Night. (In addition to making you immediately want to read Baldwin, the movie makes you want to immediately watch about three dozen other movies.) And through it all, there’s interspersed footage from events following Baldwin’s 1987 passing – the Rodney King beating, the Ferguson riots – to remind us that the more things change in America, the more, sadly and maddeningly, they stay the same. I deeply love this film. As of this article’s publication, we still don’t know whether the nominated I Am Not Your Negro will win the Best Documentary Feature Oscar tonight. But I’m pretty certain I know where my vote would have gone.

ROCK DOG

I can’t say I was excited about the prospect of the animated comedy Rock Dog, a Chinese/Korean co-production about a lovable pooch named Bodi (Luke Wilson) who yearns to escape his domineering father and constrictive life in Tibet and jam with a music-phenom kitty cat. Given that description, sweet Jesus, can you blame me?! But while I was already cheered after finding out I’d be seeing the movie with my number-one-favorite two-year-old (and her dad), I gotta say that director Ash Brannon’s outing wasn’t half as bad as I anticipated. To be sure, it’s weird as all get-out, and not always in fun-weird ways. I’m still not sure why we needed the device of Bodi’s papa (J.K. Simmons in full J.K. Simmons growl) shooting lasers from his paws, or Jorge Garcia as a sidekick who’s clearly stoned off his gourd, or Sam Elliott reprising his Big Lebowski performance as a drawling beast named Fleetwood Yak. (Yes. Fleetwood Yak. I wish I were kidding.) Still, there are some puckish jokes and decently choreographed scenes of slapstick, and amidst a lively vocal cast that includes Lewis Black, Kenan Thompson, Mae Whitman, and Matt Dillon, the eternally fabulous and hilarious Eddie Izzard, bless him, doesn’t deliver one reading that’s even remotely predictable. But as any parent or neo-parent will tell you, the best part of the Rock Dog experience was watching the movie work its occasional magic on that two-year-old pal of mine, who stayed alert throughout and repeated favorite lines and, at one point, appeared so enthralled by the on-screen action that she felt compelled to stand right up on the arm rest of the chair in front of her. Granted, that may just have been the effects of her chocolate milk, but it was a hoot either way.

COLLIDE

If you’re one of the seven or eight people who caught Collide over the weekend, a question: Which element of director Eran Creevy’s action thriller did you find the most excruciating? The narrative that found sweetie-pie Nicholas Hoult returning to his life of crime in Germany to pay for girlfriend Felicity Jones’ kidney transplant? Hoult’s and Jones’ unconvincing attempts at American accents? Jones’ mere presence? (I’m sure she’s a nice lady and all, but this is her fourth major film role in five months – enough, already.) Ben Kingsley devouring scenery as a Turkish drug lord with a solid-gold gun and discomforting crushes on Burt Reynolds and John Travolta? Anthony Hopkins, slumming in Hannibal Lecter mode, turning “sense” into a four-syllable word? Hoult’s record-time transformation into an action-flick Dale Earnhardt? The ridiculous plot twists? The laughable escapes? (At one point, Hoult and Jones face dozens of heavily armed cops surrounding their tavern, and miraculously get away by going out the back door.) For my money – and yes, I paid actual money to view this piece of crap – it was the draining abundance of chase scenes and sequences of automotive destruction that brought back to mind every witless testosterone-fest I never wanted to see again. Collide is also so lacking in self-effacing humor that when Hoult drives at 200 miles per hour on cobblestone streets, he doesn’t even have the decency to topple a fruit and vegetable cart. Instead, he crashes into a food truck. It’s just not the same.