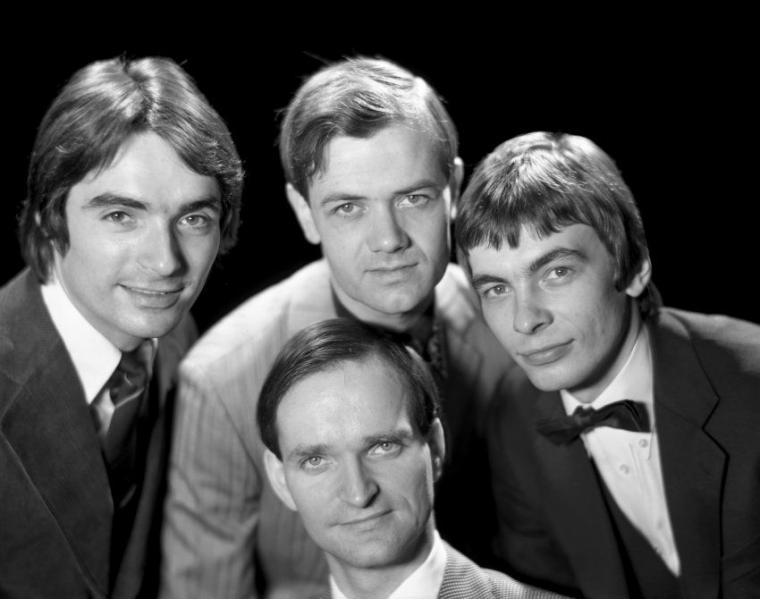

Today we learned of the passing of electronic-music pioneer Florian Schneider, a founding member of seminal German ensemble Kraftwerk alongside Ralf Hütter. Founded in 1968, Kraftwerk traces a long trajectory from the realms of experimental, electro-acoustic music focused on Schneider’s flute and Hütter’s keyboard performances into the territories of robotic electronic music built over android-vocoder vocals, repetitive synthesizer motifs, and synthetic percussion. The evolution of Kraftwerk’s music runs alongside the technological developments of the mid-20th century, and continues to influence musicians that we consider integral to many of the musical movements that have since blossomed in their wake – from techno and electronic dance music to synth-pop to hip-hop.

To attempt to summarize the influence of Kraftwerk on contemporary music as we know it is to fall into a rabbit hole of recontextualized electronic tones, sampled fragments of their music that found their way into so many classic late-20th-century recordings, and the more general approach to music as a sounding board with which to illuminate the developments of computer technology in all its forms. The impulse to canonize Schneider also faces an impasse in the fact that, despite his unquestioned status as a groundbreaking artist in electronic music, he resisted the trappings of stardom.

Schneider preferred to be perceived as an anonymous, cyborg entity within the context of music history, shunning the spotlight and living in a state of humility and frank disinterest in the media that came to acknowledge him as the iconoclast that he undoubtedly was. With his death, we come to reckon with the vast scope of his influence, and seek to shed some light on the milestones that he achieved within a landscape of popular (and unpopular) music that his hands directly guided into being.

What follows here is a selection of 10 examples of work ranging from live Kraftwerk performances, to their influential music videos, to the diaspora of their music that came to encompass so many other electronic styles that persist as major branches of music as know it.

Kraftwerk performing live at the televised Rockpalast event in Soest, Germany in 1970:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=vNoFHdlMrtI

A watershed of early electro-acoustic live performance recorded two years after the founding of Kraftwerk, this performance demonstrates the extent to which their brand of electronic-infused music already had the potential to move crowds and generate a sense of awe and futuristic wonder in their audience. The trio here comprises Schneider on electronics and flute, Hütter on keyboards and electronics, and Klaus Dinger (later of influential krautrock band Neu!) on drums. Recorded a few months after Woodstock in America and presented before a packed crowd of German concert-goers who sit spellbound, smoking cigarettes and staring into the void, Kraftwerk lay a foundation for live performance through which human beings commune with electronics, casting off peals of squalling oscillator noise and skewed keyboard noodling. The performance really picks up as soon as Dinger launches into his trademark body-animating grooves, while Schneider and Hütter begin to steer their flute, electronics, and keyboards toward more rhythmic ends. Here we see the literal genesis of techno, house music, and repetitive, groove-focused instrumental rock. The faces and body language of the crowd respond in kind to the band’s escalating rhythms, foreshadowing 50 years of fascination with electronic beats, steady kick-drum grooves, and synthesizers as lead instruments within the context of pop- and rock-adjacent music. To be among this crowd would be to rank among the first listeners ever to be exposed to electronic music in a live, widely broadcasted context, to feel your brain shifting to consider machines as viable instruments that can prod you to move your body or to zone out in equal measure.

Kraftwerk performing live on German network ZDF, 1973:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=txOxNK1nyyM

After years of re-tooling their lineup and their approach to electro-acoustic live performance, we find Schneider and Kraftwerk in another televised performance as a trio, but with much of their improvised instincts pared away to reveal an eminently melodic and rhythmic core. Schneider’s primary instrument, other than various homemade synthesizers, was the flute, and here we hear him in the role of a lead voice alongside Hütter’s constantly chiming keyboard melodies. Most revelatory here is the presence of the electronic drum kit, built from scratch as a palette of individual drum pads that can be activated with the pressure of a drumstick – foreshadowing an entire industry of drum machines, samplers, and computer percussion programs. At this level of popularity and widely disseminated broadcast availability, virtually no one in the viewing audience could have even conceived of an electronic drum kit capable of mimicking percussion sounds at this level. The fact that the band had abandoned the more free-from inclinations of their earlier music and embraced a consonant style of playing lays a groundwork for their future experiments with synthesized beats and their capacity to coexist with an ensemble of melodic voices.

Autobahn (1974):

www.youtube.com/watch?v=x-G28iyPtz0

Widely acknowledged as the bridge between Kraftwerk’s early, more freewheeling electro-acoustic experiments and the purely electronic era that cemented their legacy, Autobahn also proves to be emblematic of the group’s fascination with machines as a source of inspiration for music, here taking the form of the automobile cruising along the German Autobahn highway. Though Schneider still focused on the flute as a lead instrument, the band here has come to incorporate intricate synthesizer melodies as a main focal point. The track’s 24 minute odyssey kicks off with a cheeky recreation of a car starting and honking its horn, with the horn sound replicated on the group’s synths. From there, they wind through a series of gentle synth melodies, bubbling arpeggios, and steady percussion grooves. Though not the first Kraftwerk material to feature the human voice along with the electronic and acoustic instruments, Autobahn lays the groundwork for the group’s incorporation of dry, robotic lead vocals. Alongside a series of monotone vocal lines that proclaim the “fun fun fun on the Autobahn,” the group lays out a tapestry of melodies that never quite seems to repeat itself, always shifting into new permutations of lovely synth input and constant cyborg drum tones.

Kraftwerk live on German TV, performing “The Robots” and “Radio Activity” in 1978:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=EdubMwbOndo

Cut forward four years from Autobahn and Kraftwerk’s sound has radically changed, solidifying into more compact pop songs that feature quickly shifting chord progressions and a lattice of rhythmic synthesizer blips and percussion tones. This is one of the earliest origins of what we consider to be synth-pop today: pop music built not over instruments from the rock canon, but from electronic machines capable of replicating conventional musical scales and rhythms. By this point, the band had solidified their visual aesthetic, which came to be as singularly influential as their music. Embodying a troupe of lifeless androids that maintain a rigid upright posture and blank faces, all dressed in identical red formalwear, Kraftwerk attempt to convince their audience that they are in the “the robots” that they sing about. Most importantly, the palette of sounds here is revelatory for the future of electronic music: a steady drum beat carried by a syncopated kick drum and squelching snare tones; a web of synth arpeggios consisting of rounded sine waves and bright, upper-register square waves; the human voice modified by vocoder technology to sound electronic itself, with legible words rendered distorted and cybernetic by synth processing. The band makes the most of these televised appearances and their mimed “lip sync” recording formats to play into the role of the robotic humans that barely move in the course of their live performance, due to the fact that their machines do the work for them and have programmed sequences that repeat without direct performance. Here, Schneider still maintains his role as the band’s flautist, though his flute has been replaced by a tube-shaped synthesizer that he doesn’t even have to bring to his mouth to play. He simply taps out the songs’ iconic melodies with his fingertips, remaining totally inert and staring off into space – not unlike the audience at the band’s earliest shows, hypnotized by what they were hearing and seeing before them.

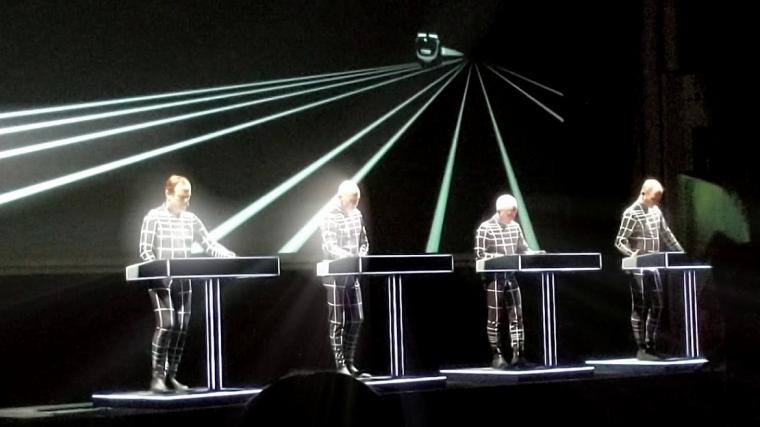

Kraftwerk live in concert, Helsinki Finland, February 2018:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=5A-4KdYSM7I

To jump ahead to modern times is to gloss over a deep catalog of Kraftwerk recordings in the “we are the robots” / Computer World style outlined above, but the band’s last tour in 2018 ends up guiding listeners through their entire oeuvre with stops at every classic album along the way. Billed as a 3D performance with a heavy integration of visuals that aired behind the band on stage, the four-piece incarnation of Kraftwerk here continues to play into the role of the cyborg performers on stage, drawing a through-line across over 40 years of performance. We see the band members slightly groove on stage as they activate electronics on their individual podiums, but the sounds here come from a palette of pre-recorded tones activated via samplers on tablets and laptops. The two-hour performance on display here counts as a spellbinding tour of their decades-worth of classic material, all enhanced by thematic visuals that shift directly in time with their music. This tour was in essence a victory lap of half a century of groundbreaking music.

David Bowie – “V2 Schneider” [Heroes, 1977]:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=miiV8WFcdwg

Shifting back to the 1970s, we begin to see the direct influence that Kraftwerk’s music had on their contemporaries from Europe and all over the world. David Bowie, then living in Berlin during the creation of his trio of seminal “Berlin Era” albums (Low, Heroes, and Lodger), became chummy with Kraftwerk during the creation of these works. The track “V2 Schneider,” named after Schneider, fuses Bowie’s anthemic glam rock stylings with the electronic tones of the Kraftwerk catalog, most evidently conveyed in the track’s synthetic drum tones, heavy use of layered synthesizer inputs, and the robotic vocal lines pumped through a vocoder that repeat the name of the track ad nauseum, as if to pay a continual tribute to Schneider and his influence on this era of Bowie’s music.

Yellow Magic Orchestra – “Technopolis” live in June 1980:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=kCwvhbhz9zU

Halfway across the world, the music of Kraftwerk was providing a direct template for further experimentation with electronic instruments in the context of pop music. Japanese trio Yellow Magic Orchestra, universally considered some of the founding fathers of synth-pop and a wide, varied industry of Japanese music, were obsessed with Kraftwerk recordings. Though they each started more in the realm of rock music and “city pop,” a form of intricate pop music performed with rock music that traced out labyrinthine chord progressions and progressive, detailed grooves, the influence of Kraftwerk led band members Ryuichi Sakamoto, Haruomi Hosono, and Yukihiro Takahashi to dive headfirst into the realm of electronic pop. If Kraftwerk’s music made the most of rigid, inhuman stylings, staccato melodies, and brittle electronic drum tones, Yellow Magic Orchestra’s music rocketed into more lush, ornate textures and more rapidly shifting harmonic frameworks. The band translated Kraftwerk’s beds of synth arpeggios into faster-paced progressions accented with warp-speed electronic melodies, classical-influenced keyboard lines, and live input on drums, guitar, and synth. Widely seen as one of the origins of the term “techno,” as it came to define electronic dance music in Detroit in the next decade, Yellow Magic Orchestra’s song “Technopolis” was an early step forward for the Kraftwerk sound, draping it in a palette of more “human” live performed elements alongside the robotic vocoder vocals.

See also: Yellow Magic Orchestra on Kraftwerk and How to Write a Melody During a Cultural Revolution (sfweekly.com)

New Order “Blue Monday” [1986]:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=FYH8DsU2WCk

If you’ve been out to a club that plays dance music in the last, oh, 30 years, you’ve encountered New Order’s “Blue Monday,” an undeniably influential exponent of the synth-pop style built over the group’s palette of “rock” instrumentation abetted by a complex web of drum-machine beats and synth melodies. A classic downer anthem as well as a classic move to hype up the crowd, “Blue Monday” represents a bridge between the post-punk style of New Order’s former incarnation Joy Division with the sonic signifiers of Kraftwerk and the synthpop movement that followed them. As if to cement the song in the Kraftwerk legacy, it contains a direct sample of Kraftwerk’s song “Uranium” from their 1975 album Radio-Activity, which you can catch at the one-minute-and-36-second mark of the song, in the layer of synthesized and smeared voice that hangs behind New Order’s intensifying network of synth passages.

Afrika Bambaataa & The Soulsonic Force - Planet Rock [1982]:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=9J3lwZjHenA

Here we backtrack a few years and cross the pond from Europe to the then-nascent scene of hip-hop in New York City. Africa Bambaataa’s hyper-influential track “Planet Rock,” produced by Arthur Baker, came into existence because Bambaataa and Baker both loved Kraftwerk, and knew that the band’s music would provide the perfect backdrop over which to rap. The track that they reconfigure here is Kraftwerk’s “Numbers” from their 1981 album Computer World. The music on display in “Planet Rock,” in addition to being a cornerstone of hip-hop production that regularly came to re-sample and re-interpret all manner of previously recorded music, also proved to be foundational to the style of dance music production known as electro, characterized by its brittle, staccato drum beats, fast-paced webs of synth input, and squishy percussion tones that land closer to purely electronic blips than to any legible sounds from an acoustic drum kit. All of these sounds originate from the work of Kraftwerk, but become reborn in electro within a more heavily syncopated, grooving rhythmic framework, with percussion elements often pumped to the front of the mix for maximum body-moving potential.

Cybotron “Clear” [1982]:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=fGqiBFqWCTU

Dancers moving to Kraftwerk “Numbers” on Detroit’s The New Dance Show in 1991:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdjEqP6mhV4

At the risk of falling into an entirely new rabbit hole that would occupy an entire many-thousand-word feature unto itself, the music of Kraftwerk directly informed the genesis of techno music in Detroit in the late '70s and early '80s. Spearheaded by a crew of closely collaborating producers known as The Belleville Three – Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson, and Derrick May – the earliest incarnations of techno music channeled the template of Kraftwerk’s synthetic beats and synth arpeggio progressions in a fashion that runs parallel to the development of hip-hop in New York around the same time. Instead of using these sounds as a template over which to rap, techno producers foregrounded the beat above all, and primed their re-interpolations to sound massive on live sound systems at dance parties.

More than a process of sampling Kraftwerk music, though, techno producers used the band as inspiration to create their own synth productions and beats using technology that was only then becoming more widely available to the public: consumer electronic synthesizers and drum machines. In a New York Times article from 2009 that examines Kraftwerk’s influence on so many modern strains of music, Juan Atkins (whose music also appeared under the name Cybotron) described the role that Kraftwerk had on his own production: “Before I heard ‘The Robots’ I wasn’t really using sequencers and I was playing everything by hand, so it sounded really organic, really flowing, really loose. That really made me research getting into sequencing, to give everything that real tight robotic feel.” Later, seminal producer and Detroit cultural icon Moodymann, though roughly a generation removed from the Belleville Three in terms of when his own productions began to emerge, explained it this way: “I thought Kraftwerk was four n----s. I ain’t going to lie to you. Until I bought that album. 'Cause 'Trans-Europe Express' used to be a skate jam; now that was classic. That was a classic motherf---ing record, and we thought that shit came out of Detroit for the longest. It wasn’t until the Robots album and we looked on there and we was like, 'What do these n----s got all this make-up on for?' And we thought that was some clown shit. We was cool with that. Then we saw videos and we were like, “These motherf---ers from Europe?' We had no clue. But we still loved their music. What I am trying to say is before we even knew where they were from, color had nothing to do it, we just loved the music.'”