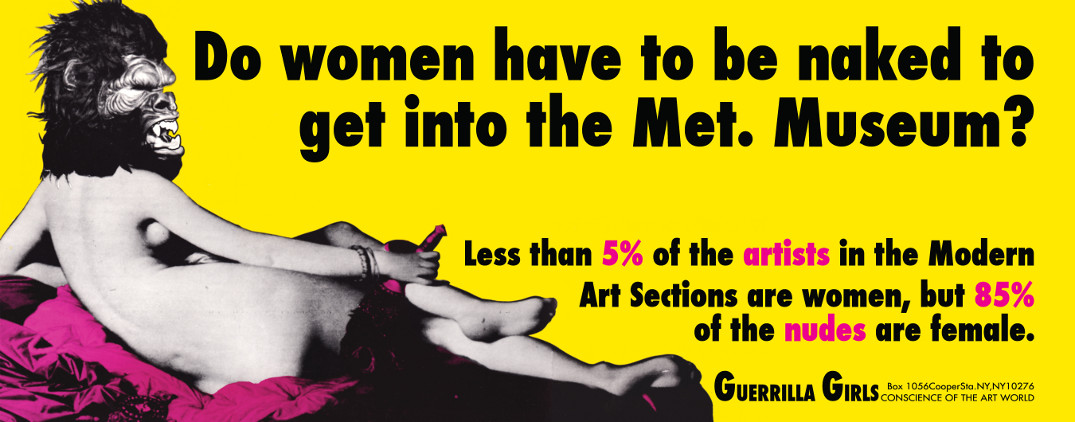

The most-famous work by the Guerrilla Girls is simple and direct, asking: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?”

The pointed text of the 1989 poster continues: “Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.”

That work is more than a quarter-century old, but the Guerrilla Girls have updated it over the years – with the results just as discouraging. The 2011 version states that women represent 4 percent of the artists in the modern-art sections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art but 76 percent of the nudes.

The work gets more complex as one considers it. The Guerrilla Girls are actually highlighting two separate disparities: a lack of women artists exhibited on the one hand, and the dominance of women among nude subjects on the other.

It features a reclining nude woman, but the image has been manipulated so that she’s wearing one of the Guerrilla Girls’ signature gorilla masks. Obscuring the subject’s face underscores the objectification of the female body both in the art world and in the larger culture.

Yet it goes a step further. The gorilla mask literally dehumanizes the subject: She is no longer a person at all, instead an alluring body with a primitive brain.

This gets to the heart of the problem. It’s not merely about numbers – that women artists are grossly underrepresented in art museums around the globe. The Guerrilla Girls are arguing that women artists are simply not considered the peers of their male counterparts. In other words, like a nude woman in a gorilla mask, female artists are treated as lesser – not worthy of serious attention.

And the lack of women artists is just one facet of a larger issue. Museums are repositories for the culture, but even now they largely downplay the voices of women, racial minorities, and other typically marginalized groups. And you can’t tell the real story of the culture through white men.

For more than three decades, the Guerrilla Girls have shined a light on these and other social inequities, focusing on but not limited to the art world. Members of the collective of anonymous female artists adopt the names of famous women artists and appear in public in those gorilla masks, and two of them will be in the Quad Cities on January 18 and 19 – for a Wednesday lecture at Augustana College and for Thursday workshops for college and high-school students.

Those programs were organized by the Augustana Teaching Museum of Art (in collaboration with Quad City Arts) and follow a fall exhibit of a Guerrilla Girls poster portfolio purchased by the museum.

Director Claire Kovacs said the Guerrilla Girls represent a new direction for her institution. “Art doesn’t just sit on a wall and be quiet and not interact with the world,” she said. “Art is this lens, it can be a catalyst, it is an active agent in the world around us, and the Guerrilla Girls’ work speaks to that so very strongly.” (See “Augustana’s Teaching Museum of Art: ‘Art Is Very Active.’”.)

The Guerrilla Girls who will be in the Quad Cities – going by the names Frida Kahlo and Zubeida Agha – said in a recent phone interview that humor has always been essential to the group’s activism, both as a coping mechanism and as a tool to start a conversation.

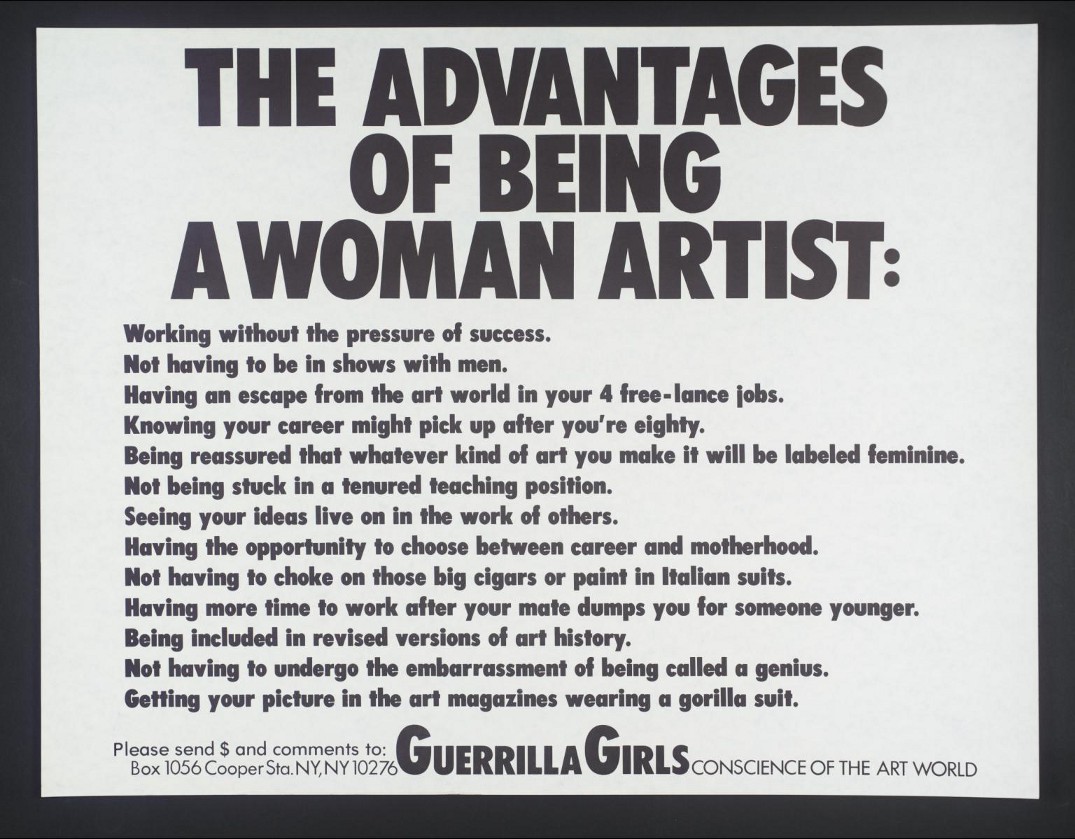

“When we were sitting around talking about this system ... that didn’t welcome us and that didn’t want us, there was a little bit of revenge in making fun of it,” explained Kahlo, a founding member of the Guerrilla Girls. “When you mock your oppressor, it gives you a kind of psychological power over them, and it might be the only power that you have. And at least it made us feel good. And it made the situation a little more tolerable.

“And then what we discovered is that if we could figure out a way to present our point of view in a humorous way to someone who didn’t agree with us, if we could get them to laugh, we knew we had their attention and we had a little opening into their thinking, and maybe we could just go in there and influence them.”

“Humor is very disarming,” said Agha, a 10-year member of the Girls.

“We were really at first treated with disbelief,” Kahlo said. “And because we were presenting the facts, and we were presenting them with an ironic twist in some way that people hadn’t thought about them before, I know for sure that our early work changed a lot of people’s minds. And we’ve always wanted the work to be transformative, and not just about preaching to the choir. ... We really want to influence the situation, and not just gather together people who already agree about something.”

“A Rigged System”

That the Guerrilla Girls have targeted the art world is no surprise given that its members are artists themselves; they’re pushing against the barriers they’ve experienced.

But it’s also important because most people consider the art world progressive. If anything, the structural sexism of museums and the art market is worse than in the world at large. And in many ways the situation is no better than when the Guerrilla Girls got going in the mid-1980s.

“If you look at the auction results that come out in the fall and in the spring, you’ll see that living women artists will get about 17 cents on the dollar of what living, white-male artists get for work of a similar importance,” Kahlo said.

(For a comparison of male and female artists at auction, see RCReader.com/y/guerrilla1. For a more-thorough overview of the status of women in the visual-art industry, see RCReader.com/y/guerrilla2.)

Agha explained that while there are progressive elements in the art world, price and income inequality are driven by the art market. “There’s this misconception that things are better in the arts. ... People within the art world always think that the art world is better, because it’s ... seen as this more-intellectual space. But art has sadly become this investment tool now. There’s so much big money involved, and that’s really perverting everything and exacerbating the problem.”

Kahlo added: “A lot of collectors and dealers who have a lot of money invested in certain artists can actually go to an auction and, if they bid up the price of one work by an artist, it means that all the other works by the same artist go up in value. So it’s kind of a rigged system.”

Because monetary value has been traditionally seen in established white-male artists, investors and collectors prize their work, which results in ever-higher prices. And because women artists and artists of color have generally had difficulty getting a foothold in the art market, their work continues to languish.

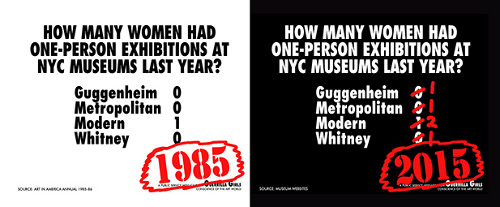

Both Agha and Kahlo agreed that it’s a vicious circle. Women artists, artists of color, and LGBTQ artists bump up against a “glass ceiling” in terms of monographs, solo shows, and museum acquisitions, and that depresses the perceived value of their work.

Those groups, Kahlo said, “really are eliminated as you walk the so-called ladder of success. And I think that leads to the largest issue, which is the issue of income inequality. Most of the money in the art world goes to artists who are white and male. ... If you don’t have equal access to the sources of production, it’s very hard to keep up.”

But she said that there has been progress. “Yes, things have changed,” she said. “In some ways, they’ve gotten better. In some ways, there are new problems.”

Kahlo said, for example, that many institutions have replaced ignoring typically underrepresented groups with tokenism: “Show one woman artist, one artist of color, one trans artist, and then think that they are diverse. That was something that kind of surprised us.”

Still, she said, the Guerrilla Girls have been successful in forcing recognition of the problem – and undermining some long-held premises: “One thing we can say that has changed is that it’s no longer assumed that the art world and art museums are a pure meritocracy. ... There were values operating inside museums that eliminated women artists and artists of color from consideration. And 30 years ago, that was a very common idea – ... it [a lack of representation] was just because their work wasn’t good enough.”

“The World Doesn’t Really Need More Guerrilla Girls”

Although the Guerrilla Girls have made their name with social-justice-themed posters and activism, they’re also a model for circumventing a system that doesn’t appropriately value their art – using their lectures, workshops, and posters to generate income.

“To be honest, it’s what keeps us alive,” Kahlo said of Guerrilla Girls lectures and workshops. “We don’t really function in the art market the way other artists do, making more and more-expensive artwork for richer and richer people.”

Museums – particularly those at colleges and universities – have collected portfolios by the Guerrilla Girls, “not as precious art objects,” Kahlo said, “but as records of the 30 years that we’ve been working.”

“It’s definitely art,” Agha said of the collective’s output. “But when we say we’re not making ‘precious objects,’ we don’t think it has to be expensive to qualify as being art. That’s a real issue that we have with the whole art industry right now, where really when people talk about art, they’re talking about the art market, and that’s a little bit ridiculous. You can make art that’s not expensive, and it’ll still be significant and valuable in making a positive impact on society.”

“Our works can exist in many places at the same time, which is kind of fascinating,” Kahlo said. “We can have three or four retrospectives of our posters going on at the same time. It can be the same work in all the shows, because our work is infinitely reproducible.”

“You could log onto our Web site right now and buy a poster for $20,” Agha said. “There is an alternative market. Your trajectory as an artist doesn’t have to be graduate from art school, find a gallery, make sure you’re in the top auctions. Because only a few can do that, and then the rest just feel like failures. You can make cheap art and live.”

That empowerment philosophy is a key part of the Guerrilla Girls’ workshops – giving people inspiration and guidance for activism.

“In the lecture, we give a brief overview of how the group got started, and we walk the audience through some of the work that we’ve done in the last 30 years and our unique approach to doing the work – how we tackle activism,” Agha said. “And then in the workshops we take it one step further where we invite the participants of the workshops to come up with their own activist – visual or theatrical – presentation. We tell them the tools that we’ve used, and then we make them use their tools and expertise to come up with something. It’s about empowering people to make change themselves. ...

“At the beginning of the workshop, we go around the room and we ask people what they’re angriest about. ... With social media, we sort of have a gauge on what people are angry about. ... But it’s reassuring to see that young people are angry about the right things.”

Kahlo added: “Our philosophy of this is sort of: Being angry is a great place to start, but it’s not a great place to finish. If you look at our work over the years, there’s a degree of craft to it. We finely tune our work so that it communicates our intention in a very direct way, and it also provokes people to think about our issues and perhaps change their minds. If you go into a project just angry, that probably won’t happen. There is a communication skill that has to be developed – an awareness of ‘How do you influence people?’”

At their appearances, of course, members of the group are often asked about the process of becoming a Guerrilla Girl.

“It’s a whole feminist trial by fire,” Agha said with a laugh before offering a genuine response. “The answer is so boring. It’s really kind of like joining a band. It comes down to a lot of mundane realities, like who’s around, who thinks the same way, who works well with everybody else, who has the time.”

“Some come forever,” Kahlo said. “Some come for decades. Some come for a couple months. And there are others who just can’t bear it and leave after a single meeting. ... I’m kind of a lifer; I don’t know how to stop.”

But they stressed that people interested in joining the Guerrilla Girls’ fight should look for other avenues.

“The world doesn’t really need more Guerrilla Girls,” Agha said. “The world needs more feminist activists. So go out and form your own group.”

“We’re bossy,” Kahlo said. “Someone with really great, fresh new ideas – why would they want to give them to us?”

Two Guerrilla Girls will appear at Augustana College’s Centennial Hall (3703 Seventh Avenue, Rock Island) on Wednesday, January 18, at 7 p.m. The free event will include a lecture and a Q&A session, and doors open at 6:30 p.m.

For more information on the Guerrilla Girls, visit GuerrillaGirls.com.