By shifting public perception, and making us believe that drug users were dangerous and a threat to America, Nixon justified his actions.

kwest/Shutterstock

On December 5, 1969, President Richard Nixon appointed Stephen Hess to the position of National Chairman of the White House Conference for Children and Youth. Hess's task was to "listen well to the voices of young Americans -- in the universities, on the farms, the assembly lines, the street corners," in the hopes of uncovering their opinions on America's domestic and international affairs. After two years of intensive planning, Hess and 1,486 delegates from across the country met in Estes Park, Colorado, and, from April 18 to 22, 1971, discussed ten areas that most concerned the youth of America. These issues included, not surprisingly, the draft and the war in Vietnam, the economy and employment, education, the environment, poverty, and, most notably for Points readers, drugs.

- Where and What Is Pottersville?

- Johnnie Carson on "African (Drug) Issues"

- Big Questions, Free Will, and Addiction

The task force on drugs, composed of eight youths and four adults, forcefully argued for addressing the root causes of drug abuse, advocating therapy for addicts rather than incarceration or punishment. "We acknowledge that drug abuse is largely a symptom of the individual's inability to cope with his immediate personal environment," they conceded. "However, it must be understood that deep societal ills increase the individual's sense of personal alienation. Specifically, our society has permitted the perpetuation of the Indochina War, of institutional and personal racism, of the pollution of our environment, and of the urban crises.... If the administration is sincere in its concern with drug abuse, it must deal aggressively with the root causes as well as implement the recommendations contained herein."

At this point, it might have been easier if Nixon had just told his Conference delegates that they couldn't have their "root causes" cake (even with its concessionary 'individual inability to cope' icing) and eat it too: There was only so much federal funding to go around. Just three months after the Youth Conference met, Nixon launched a drug war that framed drug users not as alienated youths whose addiction was caused by inhabiting a fundamentally inequitable society, but as criminals attacking the moral fiber of the nation, people who deserved only incarceration and punishment.

Long before William Bennett wrote that the root cause of crime was moral poverty (and well after Richmond Hobson called drug users the vampires of society), Nixon was chewing on the same meaty ideas, privileging the view that drug abusers were criminals and decreasing social welfare funding would therefore attack the root causes of drug abuse. This criminalization of drug users launched a trend; Nixon's was one of the last administrations to spend more on prevention and treatment than law enforcement and nearly every administration since (with the exception of Jimmy Carter's) worked to increase the division between prevention and enforcement spending. This division has become the core of our modern war on drugs. After all, why finance a war on poverty when there's a politically popular war against crime to fund? This tension has a long and complex history. As any scholar of addiction or drug history knows, Nixon wasn't the first president (let alone the first person) to ponder the question of whether drug abusers were victims of their environment or of their own personal vice. David Courtwright, Arthur Benavie, James Inciardi, David Musto, and Caroline Acker and Sarah Tracy, among many others, have traced America's two-century quest to figure out what lies behind a person's abuse of chemical substances. These scholars have written excellent texts showing how, historically, the pendulum has repeatedly swung between these two poles. They've also shown how, through the ages, the specter of drug abuse has been a presented as a cause (or a whipping boy) for the ills of the era. It was Nixon's drug war in the early 1970s, however, where the drug-user-as-culpable-source-of-crime exploded into view. Since this image has come to underscore the drug policies that Republican presidential contenders are currently debating right now, and given that it informs much of our current era of drug law confusion, we must attempt to understand the origins of this debate.

In Nixon's eyes, drug use was rampant in 1971 not because of grand social pressures that society had a duty to correct, but because drug users were law-breaking hedonists who deserved only discipline and punishment. After all, this was the same man who argued in "What Happened to America?" (published in Reader's Digest in 1967) that, when it came to punishing rioters in Detroit and Newark, "our opinion-makers have gone too far in promoting the doctrine that when the law is broken, society, not the criminal is to blame." This view appealed to Nixon's "Silent Majority," his core constituency of voters who had grown tired of shouldering the blame as drug use grew rampant and violence tore inner cities apart.

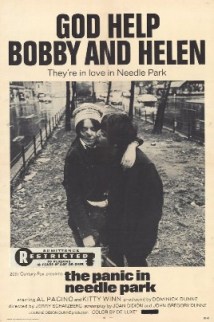

To be fair, drugs clearly were a problem in 1971 (I mean, did you see Panic in Needle Park?), even if the Nixon administration distorted the numbers that tied drug addiction to instances of crime. Shifting the conversation away from eradicating the causes of crime and focusing solely on punishing the criminal, the 'Law and Order' President was able to do two things: First, Nixon exonerated the white middle class from responsibility for the drug-related violence ravaging the inner cities. Second, he transformed the public image of the drug user into one of a dangerous and anarchic threat to American civilization. Shifting public perception in this way ultimately served to reinforce the 'necessity' of Nixon's drug war. Once addicts were no longer seen as sick victims of a society that systematically excluded them, no one would mind when they were simply locked up. In fact, incarceration was for the nation's own good.

In some ways, one can understand this shift in social terms. The issue of drug addiction has long straddled the line between being framed as a medical, political, or moral issue. Richard Nixon simply presented his stance in terms that appealed specifically to his conservative base. Andrew Hacker, in his 1973 article "On Original Sin and Conservatives," summed up the "'personal culpability" argument succinctly when he claimed that conservatives believe that "man is infected by the virus of Original Sin," and that we are all "prone to perversity; that the best-intentioned plans will have self-defeating consequences; that no society can ever attain consensus." Worse still, "to assume that we know enough to diagnose causes (derelict housing, bad schools, unemployment) or to bring about cures (jobs, slum clearance, better education) is a monumental delusion. The conservative prescription is to bring criminality under control."

This is precisely the ideology that underscored all of Nixon's drug war policies and allowed him to present himself as the moral solution to failed liberal initiatives. It was a delusion, as Hacker points out, to assume that we could cure social problems that are, at root, lapses in moral judgment and the mark of original sin. The addict doesn't need to be cured. Rather, he needs to be contained before he can do any additional harm. Launching a war that emphasizes forfeiture and "no-knock" drug busts over rehabilitation or treatment is the most logical outcome of this reasoning, one that we've endured since 1971.

In the early 1970s, the battle against drug abuse touched upon all of the nine realms that troubled the delegates at the Youth Conference. Poverty, the economy, jobs, Vietnam, and education -- all were deeply tied up in Nixon's war on drugs, even though the answers the delegates arrived at found cold reception from the administration itself. It was here, in the late 1960s and early '70s, when drug use became a visibly powerful post-war political trope, an element of Nixon's southern strategy and an epidemic that served as an excuse to overturn a decade of social welfare spending and replace it with increased law enforcement and police surveillance. And it was during Nixon's administration-and-a-half where the believers in "personal culpability" were distinctly sundered (and, in Nixon's case, privileged) from those liberal progressive supporters of "root causes," bringing to a close the Great Society's desire to eradicate the causes of crime rather than just the criminal himself.

In the early 1970s, the battle against drug abuse touched upon all of the nine realms that troubled the delegates at the Youth Conference. Poverty, the economy, jobs, Vietnam, and education -- all were deeply tied up in Nixon's war on drugs, even though the answers the delegates arrived at found cold reception from the administration itself. It was here, in the late 1960s and early '70s, when drug use became a visibly powerful post-war political trope, an element of Nixon's southern strategy and an epidemic that served as an excuse to overturn a decade of social welfare spending and replace it with increased law enforcement and police surveillance. And it was during Nixon's administration-and-a-half where the believers in "personal culpability" were distinctly sundered (and, in Nixon's case, privileged) from those liberal progressive supporters of "root causes," bringing to a close the Great Society's desire to eradicate the causes of crime rather than just the criminal himself.

While not all conservatives have consistently adhered to this view (after all, the National Review published an opinion piece in 1996 that claimed decisively that the "war on drugs is lost" and, as we all know, Ron Paul defies all stereotypes), this dichotomy perpetually exists and has influenced our drug and culture wars from Nixon's administration to today.

Since historicizing current conundrums never did anyone any harm, I hope you'll hang out with me for the next few days as we explore the myriad origins of one of drug policy's most meaningful debates. In my next post we'll explore the role religious anti-drug activism in the immediate post-war era played in this ongoing discourse. And we'll also answer the fascinating question, What do David Wilkerson, Paul Goodman, and Pat Boone all have in common? The answer is awesome!

This article originally appeared on Points, an Atlantic partner site.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.